The Political Thought of Abraham Lincoln

Allen C. Guelzo

Hertog Foundation | 2015

When Americans are asked to rank their presidents, Abraham Lincoln almost always comes out at the top. But why? Sometimes, the reason is that he freed the slaves…or that he saved the Union . . . or that he was a great war president . . . or that he was a master of words . . . or the model American. All of these are true. But these truths don’t quite get at the man behind these truths. Although Lincoln had next-to-nothing in the way of formal education, he possessed a natural intellectual curiosity, a voracious appetite for reading, and a passion for ideas, political and otherwise. And although he was not an intellectual, he had a profound grasp of the basic principles of the American Founding, and how they were to be applied in the great clashes of ideas in the 19th century about religion, politics, Romanticism, race, and slavery. In this seminar, we will see how Lincoln was shaped by five important issues in his day:

- The Legacy of the Founders: Lincoln considered Washington and Jefferson as the pole stars by which he steered politically. “Washington is the mightiest name of earth—long since mightiest in the cause of civil liberty; still mightiest in moral reformation,” Lincoln said in 1842, “To add brightness to the sun, or glory to the name of Washington, is alike impossible.” Likewise, he added in 1859, “The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society.” The question for Lincoln was how these principles were to be preserved in a rapidly changing environment when confidence in the viability of the American experiment was being challenged, both from within (by American slavery) and from without (by the rebirth of aristocracy and empire in Europe).

- Economic Liberty: Lincoln considered economic opportunity to be the nuclear core of American liberty. The underlying purpose Lincoln discerned in “the toils that were endured by the officers and soldiers of the army, who achieved . . . Independence” was not “the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the mother land; but something . . . which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.” That something was the equality of economic opportunity, which encouraged social mobility and self-transformation for everyone. “We stand at once the wonder and admiration of the whole world,” Lincoln said in 1856, because in the United States, “every man can make himself.” In this way, Lincoln not only linked himself to the American Founding, but to the promoters of classical liberalism in England in the 19th century, especially the so-called ‘Manchester School.’

- The Challenge Posed by Slavery: Lincoln insisted that he had always hated slavery, and committed himself politically to the extinction of slavery. But this desire to abolish slavery was motivated by more than an abstract empathy for an oppressed racial minority. Lincoln considered as slavery any form of economic arrangement which denied people mobility, self-transformation, and the enjoyment of the fruits of their labor.

- Religion: Lincoln was raised in a devout religious environment and carried the stamp of that religious upbringing all through his life. But he was also a rebel against religion, and tried to shape his life according to the 18th-century Enlightenment’s model of ‘reason.’ Yet, in his great debates with Stephen A. Douglas, he appealed to natural law and natural rights, and in the depths of the Civil War could find no ‘reasonable’ explanations for the course of events. In the end, Lincoln found himself bringing religion and morality to bear on public policy in a way that no president before (or since) has done.

- The Survival of Constitutional Democracy: When Lincoln described the Civil War as test of whether “this nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure,” it was not mere rhetoric. By the time Lincoln becomes president, the United States is the only successful, large-scale democracy in the world. Not only does the Civil War make democracy appear unworkable, it challenges the survival of the very Constitution Lincoln was sworn to uphold and defend. He must find a way to wage a principled war against the foes of democracy, yet do it in such a way that does not endanger the constraints the Constitution placed on his office and the national government.

This seminar will be an exploration of Lincoln’s mind—of the great intellectual problems he faced, of the books he read, of the ideas he defended, and of the kind of democracy he thought was worth saving. And at the end, we will come to know Lincoln, not just as the greatest of presidents, but as a man of great ideas as well.

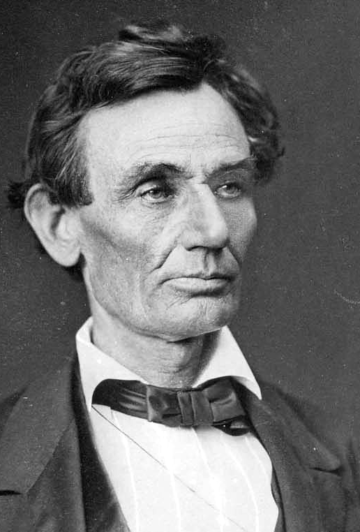

“Abraham Lincoln” by Alexander Hessler, courtesy of the Library of Congress