The Writings of Booker T. Washington

Study the moral vision & subtle statesmanship of Booker T. Washington.

June 30–July 4, 2025

Washington, DC

The third week of Political Studies will engage key texts that have helped shape the political idea—and political ideals—of America.

The first section will explore the political significance of the year 1776 through a remarkable set of contributions to political theory: books by Edward Gibbon and Adam Smith, pamphlets by Thomas Paine and Richard Price, poems by Phillis Wheatley—and, of course, Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

The second section will engage the ideas of modern liberal democracy, exploring how the American system has sought to balance the deepest themes of ancient political thought against the imperatives of individual freedom, security, and economic progress that are so central to modern liberal thought.

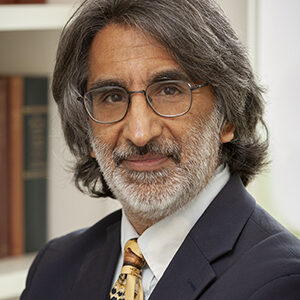

Ryan Hanley on the ideas of 1776

This course is part of our residential Political Studies Program. Fellows participate in morning seminars and meet prominent men and women in public life over afternoon and evening sessions. Up to 32 fellows will be selected.

Ryan Patrick Hanley is Professor of Political Science at Boston College. His research in the history of political philosophy focuses on the Enlightenment. He is the author of Our Great Purpose: Adam Smith on Living a Better Life and Love’s Enlightenment: Rethinking Charity in Modernity.

Ryan Patrick Hanley is Professor of Political Science at Boston College. Previously, he was the Mellon Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Marquette University. His research in the history of political philosophy focuses on the Enlightenment.

He is the author of Our Great Purpose: Adam Smith on Living a Better Life (Princeton University Press, 2019), Love’s Enlightenment: Rethinking Charity in Modernity (Cambridge University Press, 2016), and Adam Smith and the Character of Virtue (Cambridge University Press, 2009). His edited volumes include Adam Smith: His Life, Thought, and Legacy (Princeton University Press, 2016), the Penguin Classics edition of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (Penguin, 2010), and with Darrin M. McMahon, The Enlightenment: Critical Concepts in History, 5 vols. (Routledge, 2010).

His articles have appeared or are forthcoming in American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, European Journal of Political Theory, Review of Politics, Social Philosophy & Policy, History of Political Thought, Journal of the History of Philosophy, Revue internationale de philosophie, and Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie.

Professor Hanley received his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania, his M.Phil. from Cambridge University, and his Ph.D. from the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. Prior to Marquette, he was a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Yale University’s Whitney Humanities Center.

Wilfred M. McClay holds the Victor Davis Hanson Chair in Classical History and Western Civilization at Hillsdale College. His book, The Masterless: Self and Society in Modern America, received the 1995 Merle Curti Award of the Organization of American Historians for the best book in American intellectual history.

Wilfred M. McClay holds the Victor Davis Hanson Chair in Classical History and Western Civilization at Hillsdale College. Before coming to Hillsdale in the fall of 2021, he was the G.T. and Libby Blankenship Chair in the History of Liberty at the University of Oklahoma, and the Director of the Center for the History of Liberty.

His book, The Masterless: Self and Society in Modern America, received the 1995 Merle Curti Award of the Organization of American Historians for the best book in American intellectual history. Among his other books is The Student’s Guide to U.S. History, Religion Returns to the Public Square: Faith and Policy in America, Figures in the Carpet: Finding the Human Person in the American Past, Why Place Matters: Geography, Identity, and Public Life in Modern America, and Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story.

He served for eleven years on the National Council on the Humanities, the advisory board for the National Endowment for the Humanities, and is currently is a member of the U.S. Commission on the Semiquincentennial, which has been charged with planning the celebration of the nation’s 250th birthday in 2026.

He has been the recipient of fellowships from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Academy of Education, and served as a Fulbright Senior Lecturer in American History at the University of Rome. He is a graduate of St. John’s College (Annapolis) and received his Ph.D. in History from Johns Hopkins University.

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Readings:

Discussion Questions:

Diana Schaub

Diana Schaub is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where her work is focused on American political thought and history, particularly Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, African American political thought, Montesquieu, and the relevance of core American ideals to contemporary challenges and debates. Concurrently, she is Professor Emerita of Political Science at Loyola University Maryland, where she taught for almost three decades.

Judge Roy Altman

Judge Roy K. Altman, at 36, became the youngest federal district court judge in the country—and the youngest federal judge ever appointed in the Southern District of Florida. He received his BA from Columbia University and his JD from Yale Law School, where he was projects editor of the Yale Law Journal. After law school, Altman clerked on the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals for the Honorable Stanley Marcus.

Akhil Reed Amar

Akhil Reed Amar is Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, where he teaches constitutional law in both Yale College and Yale Law School. He is Yale’s only currently active professor to have won the University’s unofficial triple crown — the Sterling Chair for scholarship, the DeVane Medal for teaching, and the Lamar Award for alumni service. He hosts a weekly podcast, Amarica’s Constitution.

Adam J. White

Adam J. White is the Laurence H. Silberman Chair in Constitutional Governance and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on the Supreme Court and the administrative state. Concurrently, he codirects the Antonin Scalia Law School’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State.

Robert C. Bartlett

Robert C. Bartlett is the Behrakis Professor of Hellenic Political Studies at Boston College. His principal area of research is classical political philosophy, with particular attention to the thinkers of ancient Hellas, including Thucydides, Plato, and Aristotle. He is the co-translator of a new edition of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

William Kristol

William Kristol is editor at large of The Weekly Standard, which, together with Fred Barnes and John Podhoretz, he founded in 1995. Mr. Kristol has served as chief of staff to the Vice President of the United States and to the Secretary of Education. Before coming to Washington in 1985, Kristol taught politics at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

Rita Koganzon

She is an associate professor at the School of Civil Life and Leadership at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the themes of education, childhood, authority, and the family in historical and contemporary political thought. In addition to her research, she contributes book reviews and essays to the Hedgehog Review, National Affairs, The Point, and The Chronicle of Higher Education, among others.