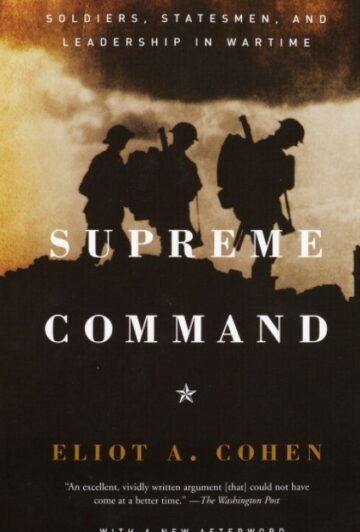

The relationship between military leaders and political leaders has always been a complicated one, especially in times of war. When the chips are down, who should run the show — the politicians or the generals? In Supreme Command, Eliot Cohen examines four great democratic war statesmen — Abraham Lincoln, Georges Clemenceau, Winston Churchill, and David Ben-Gurion — to reveal the surprising answer: the politicians. Great states-men do not turn their wars over to their generals, and then stay out of their way. Great statesmen make better generals of their generals. They question and drive their military men, and at key times they overrule their advice. The generals may think they know how to win, but the statesmen are the ones who see the big picture.

Lincoln, Clemenceau, Churchill, and Ben-Gurion led four very different kinds of democracy, under the most difficult circumstances imaginable. They came from four very different backgrounds — backwoods lawyer, dueling French doctor, rogue aristocrat, and impoverished Jewish socialist.Yet they faced similar challenges, not least the possibility that their conduct of the war could bring about their fall from power. Each exhibited mastery of detail and fascination with technology. All four were great learners, who studied war as if it were their own profession, and in many ways mastered it as well as did their generals. All found themselves locked in conflict with military men. All four triumphed.

Military men often dismiss politicians as meddlers, doves, or naifs. Yet military men make mistakes. The art of a great leader is to push his subordinates to achieve great things. The lessons of the book apply not just to President Bush and other world leaders in the war on terrorism, but to anyone who faces extreme adversity at the head of a free organization — including leaders and managers throughout the corporate world.

The lessons of Supreme Command will be immediately apparent to all managers and leaders, as well as students of history.